Image Credit:

I’m teaching an upper-division rhetorical theory course about legal rhetoric in which I focus students on the rhetoric involved in adjudicating particular cases in dispute. The initial unit in the course focuses students on the rhetoric of narrative, memory, and proof surrounding factual disputes in particular cases. Although there are many examples of such discourse, the most classic example is in a legal trial. My goal in the unit is to illuminate certain common topics, or topoi, of forensic discourse as well as to illuminate the contingencies in factual disputes that create opportunities for persuasion. At the conclusion of the unit, the students write a 1,000-1,500 word paper in which they rhetorically analyze opposing arguments regarding an evidentiary controversy in a forensic dispute, which in the context of the course nearly always means a trial. The assignment specifically requires that in addition to a primary source for the arguments the paper analyzes, the paper must include a primary source of the evidence in dispute. This latter source typically includes trial exhibits such as photographs or video and/or the testimony of trial witnesses reflected in a trial transcript. Trial transcripts, however, can be difficult to locate and access.

As a result, toward the end of this unit I conduct an online research tutorial with my students in class designed to assist them in accessing trial transcripts and excerpts from such transcripts. In an electronic classroom in which each student has access to a computer with internet access, I first show students the location and search features of various online resources for trial discourse. One of the greatest sources for such discourse is the Clarence Darrow Digital Collection, which provides free online access to complete word-searchable trial transcripts from the most famous cases of one of America’s greatest trial lawyers. Two other great free online trial archives are the Proceedings of the Old Bailey, 1674-1913, containing details regarding 197,745 criminal trials held at London's central criminal court, and Douglas Linder’s Famous Trials Site, which includes excerpted arguments, trial testimony, and exhibits from numerous famous trials. In addition, certain paid databases available through the University of Texas at Austin contain trial records, such as Hein Online’s World Trials Library and Gale’s Making of Modern Law: Trials, 1600-1926. I also point students toward the print volumes in the extensive Notable Trials Library series, many volumes of which contain extensive excerpts from the trial transcripts in a large number of famous trials, as well as other print sources for opening and closing arguments from famous trials.

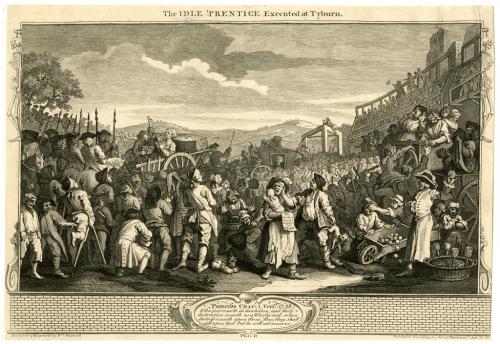

As a conclusion to this online research workshop, I have students explore the rhetoric of 18th-19th century crime broadsides from the Harvard Law School Library's online collection of crime broadsides. Beyond teaching additional online research skills regarding legal rhetoric, the goals of this assignment are to further a discussion of the symbolic aspects of legal rhetoric, or how legal rhetoric operates not only to decide the outcomes of legal cases but to shape communal values and norms. To accomplish this, I have students conduct an in-class rhetorical analysis of the texts and images in the database. These materials describe crimes and the apprehension of criminals during the 18th-19th century when such information was widely disseminated in broadsides and public discourse regarding the investigation of crimes common. The assignment both reinforces the availability of many interesting forms of legal discourse online and generates engaging class discussion.

To begin the assignment, I introduce students to the Harvard Law School Library's online collection of crime broadsides. With students at their computers, I demonstrate the site's search features and discuss a couple of sample broadsides as a tutorial of the site. I inform students that their task is to isolate and analyze the ways in which norms and identity are rhetorically constructed in one of the broadsides from the site. The remainder of the class is then devoted to students conducting their own research and posting their broadsides along with a brief rhetorical analysis to a course blog to which they regularly post other assignments. The blog posts may then be discussed collectively as a class with or without requesting individual students to present on their broadsides and analysis. This assignment can be completed in a single class period or span two class periods, depending on the details of the assignment.

I don’t grade the assignment but use it as an encouragement to collectively explore and comment on some fascinating documents regarding the public rhetoric surrounding particular cases of crime. It's primarily designed to engage students in questions considered during the course and to facilitate class discussion. I've used this lesson plan with two classes and both groups of students found the broadsides and their rhetoric fascinating and enjoyed the assignment. Their contributions have been consistently engaged and insightful. The assignment not only provides a thought-provoking ending to what can sometimes be a tedious research tutorial, but has helped me to simultaneously teach online research skills, generate interest in the materials contained in online archives, and illuminate the cultural significance of forensic rhetoric beyond instrumental problem-solving motives.