Image Credit:

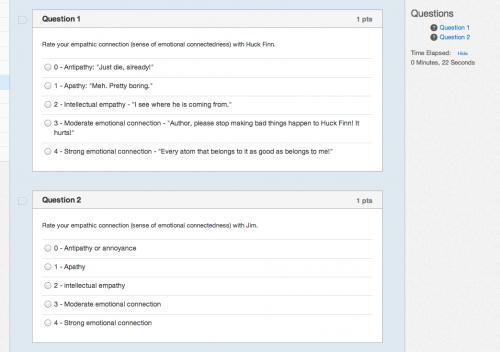

Survey created in Canvas.

This semester, I taught a Banned Books class focusing on the ways that authors deploy empathy. One cornerstone of the class was a series of daily surveys. Each discussion was preceded by a survey (pictured above) in which students gave an informal ranking of their empathetic response to the main character(s) featured in the day’s readings. My goal was to help students theorize their own responses to stories, but I also ended up generating some unexpected revelations.

The surveys about The Satanic Verses went as I expected, but not as my students expected, which provided a valuable learning opportunity. Initially, the novel’s two Indian protagonists were too alien for students to initially identify with them. As a result, student empathy with both characters increased as they found themselves capable of projecting their own identities into Saladin Chamcha and Gibreel Farishta. Halfway through the book, however, they were surprised to find their ability to empathize with the characters to be dramatically undercut. My general conclusion is that this dropoff was caused when the details of Rushdie’s novel began to violate students’ expectations of the character. The students own responses, however subjective or imprecise, allowed me to introduce the concept of “false empathy,” where a deep sense of empathic connection actually serves to blind students to the realities of these characters. The temporary drop in students’ empathy, then, might actually reflect better reading practices, as they deconstruct false images of the character and began to grapple with the unfamiliarity of the characters. This in turn lead to better, perhaps less false, empathy. Most students ended up reporting their strongest connections with the characters as they concluded the novel.

The graph for Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, unfortunately, was less enlightening—probably because I chose the wrong character. I had my students rate their connection not with the traumatized Pecola, but with the book’s primary narrator, Claudia. Since her character was not particularly dynamic, students quickly built up empathy for her and stayed quite empathetic. In fact, the only point of interest was a related poll I did on students reactions to the aged child molester who appears later in the book; those results, however, are beyond the scope of this discussion.

Huckleberry Finn generated the most interesting results, managing to truly surprise me. This was true not in the overall graph, but in the details. Generally, Huck followed a similar sine-curve pattern to Gibreel and Saladin, while the less complex (and more passive) escaped slave Jim consistently gained empathy in a linear pattern close to that of Claudia. Yet on the day that students read about Huck’s climactic decision to free Jim even if it meant embracing a life of wickedness, something interesting happened.

Above, you can see a more detailed breakdown of student’s responses before and after they read Chapter 31. Before, most students felt a sense of “moderate emotional connection” with Huck. That is, they felt emotionally tied to Huck Finn’s fate, but they didn’t identify with him on a deep level. After Chapter 31, the class polarized. A narrow majority, as I suspected, responded to Huck’s troubled theological and ethical musings by doubling down on their emotional investment in the character, reporting a newfound “strong emotional character.” But a very significant portion of the classroom found the chapter distancing. They reported being able to “see where he [Huck Finn] was coming from” intellectually, but they lost (at least temporarily) their ability to empathize with Huck.

Charting empathy using an online survey at the beginning of class turned out to be not only a great teaching opportunity, but a great learning opportunity. It certainly didn’t provide rigorous data, and I would be hesitant to make any firm claims based on such an informal series of surveys, but it did provide something valuable: a new way of thinking about how students read, and a series of talking points allowing students to reconsider the nature of their empathic connections with fictional characters.