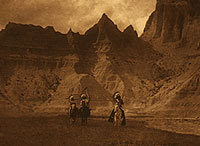

Image Credit:

In the Bad Lands Edward S. Curtis The North American Indian (vol.3)

As graduate students, we know we’re fortunate to work at a university with a world-renowned public archive. We have David Foster Wallace’s papers, the Magnum Archive Collection, and too many other treasured cultural pieces to even begin to name them. We visit the archive to research and become inspired, so why not bring our own undergraduate students to share in the wealth? Thanks to the Harry Ransom Center’s current policy, with careful planning, instructors are permitted to bring their classes to the archive so that undergraduate students can enjoy these same materials. In this post, I’ll share some tips to help my fellow instructors to make the most out of your time should you decide that holding a class meeting in the Harry Ransom Center might add something extra special to your seminar.

My first bit of advice to instructors is to familiarize yourself with proper protocol. If for some reason your area of research has never led you to handle rare manuscripts, books, or photographs, take time to register for an account with the Harry Ransom Center and watch the training video which takes about 20-30 minutes. Be sure to ask staff or librarians on duty for help if at any point you’re uncertain of how a material should be handled. Also, if you’ve handled materials at archives elsewhere, keep in mind that different archives have different policies. It should also be noted that I am in no way affiliated with the Harry Ransom Center, and that these policies may change over time, so you should always check with librarians and staff first.

The thing I would emphasize most to my peers is that holding a lesson in the Harry Ransom Center requires advanced planning. Current policy stipulates that instructors ask to reserve the room one month in advance, and to request visual materials two weeks in advance. You can find more details by checking out the Harry Ransom Center’s website: http://www.hrc.utexas.edu/research/forms/rooms/guidelines/

Now that you know the most crucial detail: that you must plan this event at least a month ahead, you’ll want to ask yourself if the visit is truly worthwhile for your particular seminar. For almost any humanities class, I would say that it is, but because the center has strongest holdings in the 20th century, this might not be the case for those solely studying 21st century topics, which may or may not be represented in the archive to a level that would be useful to your class. So really, the first step is to assess what you’ll be teaching that day at least one month in advance. The second step is to pick the specific lesson plan which you think would benefit the most from the presence of primary materials.

When it comes to picking out the materials for your class, I recommend that instructors set aside at minimum two hours to look through materials. It will take time for staff to retrieve your request, and to bring it to you. Because students generally would not be permitted to touch things in the room, you’ll need to flag any specific pages of books which will then be left open to the desired page in a cradle on the day of your class meeting. If you plan to use photographic prints or art, remember that these are often stored in large portfolio boxes which you will need to slowly look through, carefully moving one print at a time, until you’re able to locate and flag your desired print. Also, this process is generally enjoyable, so give yourself time to look through all of the rare manuscripts, books, or photographs in fron of you.

In class sessions leading up to the Harry Ransom Center meeting, instructors will probably want to inform students about proper protocol so as to save time once you arrive and ensure everything goes smoothly. Stake out a designated meeting spot and let the group know what to expect in terms of stashing valuables in cubbies, and not bringing food or drink. As you tell them about proper decorum, also be encouraging. In my experience I found that my students (like anyone) seemed impressed by the solemnity of the archive in a way that could hinder discussion. So, it’s important to carefully walk that line between inculcating a sense of expected behavior so as not to disrupt patrons or damage valuable materials, without wasting the student’s cognitive space in a way that would limit free thinking or discussion.

Here I’ll share my particular lesson plan just in case it helps other instructors. For my class “Rhetoric of Photography,” visiting original photographic prints and books was a mid-semester treat. For the big day, I picked a time slot in the middle of our second unit: “Photographing Others” just after our lesson on street photography and in time for our lesson on ethnographic photography. I chose this because I had already seen the Harry Ransom Center’s prints from both Henri Cartier-Bresson as well as Edward S. Curtis, and knew that the center had excellent holdings for both. I prepared a short Powerpoint presentation, rented a documentary on the life of Edward S. Curtis called Coming to Light: The Edward S. Curtis Story to play snippets from, and prepared some discussion questions. It was basically an ordinary lesson plan, but with added time for viewing the original prints, and perhaps more detailed focus on some conversations around authenticity we’d had earlier in the semester, coupled with added attention to the physicality of the prints and the photo-making process, which we hadn’t discussed as much for lack of older photographic prints.

Fortunately, the students seemed to be pretty excited to be around primary materials. So, we started class with a large loop around the whole room giving everyone a chance to get a good look at the materials. That way, they would have a detailed image in mind as we discussed the work, and also would feel that they had time to make a sufficient connection with the artifact. Perhaps the most popular print was one I requested from our first unit on iconic photos, “Migrant Mother.” Students really seemed enthused to see the photo, which led to lots of Benjaminian conversations about authenticity – “here it is!" "The real thing!" "Is it the real thing?” "Is there an original?"

Mostly, I like this assignment, because I think it makes the students feel special. As humanities teachers we walk a line between being custodians of culture and mentors. In that “custodian of culture” role, and especially in the archive, sometimes the artifact itself is the mentor. It’s probably true for most of us that we were inspired to study literature or rhetoric because we felt a connection to excellent professors in our past, but most of us also found this path because (with or without the guidance of a teacher) we felt a connection to authors and artists from before our time (contemporary lit. people, your role is complicated here). As teachers, we never know exactly who we’re teaching, or what poem or image will resonate with a student. Unless we build a lasting friendship, we don’t know what that student will go on to do, or what materials might inspire them to change the trajectory of their career, their lives, or (why not think cosmically?) human history.

Many of us interested in the digital humanities are passionate about accessibility for some of these very reasons. When that archive is already present in your own backyard though, you may as well visit the original. This isn’t to place the digital archives and physical archives in a hierarchy: the two serve a different purpose, one that I don’t mean to limit to convenience or geography. In the past, I’ve found digital archives useful for more interactive plans where the class might mark a text up as a group at the same time, or pull up two editions of the same text on the screen for a quick side by side comparison. In this case, I might prefer to show my students a primary work online, even when it was available in the Harry Ransom Center. Digital archives can be excellent resources in the classroom, but real archival materials are useful for learning about other things. In a class held in a physical archive there are simply different strengths. One can examine the composition of the object: the sheen of a Curtis gelatin silver print which can’t be seen online, the size of the print, or, if you’re superstitious, interested in discussing authenticity, or both – there’s endless merit to merely being in the presence of the object.

Perhaps in a future post I’ll get the chance to say more about the pros and cons of teaching from digital archives vs. physical archives, as I think there’s a lot to be said for the use of both in the classroom.