Image Credit:

This blog post is a “coming-out” [1] story—the story of teaching in a classroom of hearing students as a Deaf [2] teacher and what that means in terms of methodology. It is a “coming-out” story because it involves processes of choosing to “come-out” (as Deaf identity is invisible until some aspect comes to play to disrupt the “hearing line.” [3]) This blog post also aims to make clear the abilities of D/deaf teachers, to explain the differences (small from my perspective) between Deaf and hearing teachers, and to detail the benefits of the Deaf teacher in a hearing classroom with regards to power dynamics.

I also aim to lay out questions of embodiment and how the choices of the D/deaf teacher affect, rely on, and consider power dynamics not only between the teacher and the students, but also with relation to the cohort of teachers within an institution. As I do this, I hope to answer common questions about my pedagogical choices (with regards to questions of abilities and implied commonplaces about teaching hearing students). I have asked several of these questions of myself as my teaching practices evolved and as I developed more confidence as both a teacher and a graduate student without a cohort who could fully relate to or understand my position as a Deaf teacher.

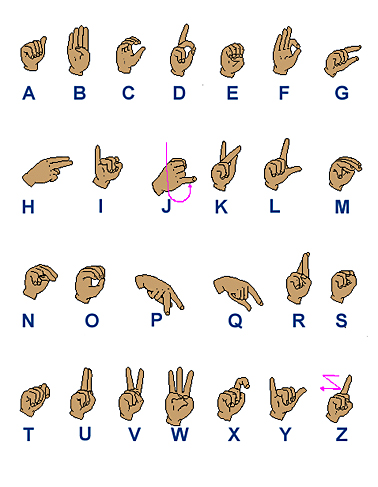

On the most basic level, the difference between hearing teachers and myself is one of language modality—it is a difference that relies on questions of access and language dominance. My first language, American Sign Language (ASL), is a minority language. Yet, I teach and talk about the dominant language of English, the language of our institution, of our department, and of our course content. I can do this because I am bilingual. However, because I am Deaf, I must consider my options for teaching hearing students. Because I speak English well enough to “pass” as a hearing person (with most audiences), I must choose when to “come out” as a Deaf person. And, because I do not hear well enough to understand everything that is spoken—especially in large group settings—I have full access to language only when it is visual. Hence, on the most basic level, I require, or have the most access to what is said in a classroom when I either read or see the words spoken. Having tried CARTs, or Communication Access Real-time Translation, in a few lecture classes and in a conference setting, I find that I prefer seeing language on the hands, and I work with ASL interpreters who sign what my students say and speak what I sign.

Returning to the idea of “coming out” and questions of abilities, the way I present myself when I first meet a person sets the expectation for the remainder of our communicative interactions. When I first began teaching—way back in high school—I strove to mold myself in such a way as to fit my students. This chameleonic work meant that when I taught hearing preschoolers and middle school students, I did so without interpreters. I “passed” as hearing and never came out as a Deaf person. The mentor that I worked with might perceive me as deaf because she knew me as a deaf student from her other classes, in which I had interpreters, or I might “come-out” to my mentor as a hard-of-hearing (hoh) person, but I would never come out to my students. I thought it most important that I focus on my students’ needs and that I appear like them. Conversely, when I tutored D/deaf high school students in the writing center, I signed and presented myself as a Deaf/hoh student like them. But, when a hearing high school student came in, I switched right back to spoken English, and if they did not already know me, they saw me as another hearing tutor who worked in the writing center. However, even as my Deaf identity was invisible to most, it was never invisible to me, and I had to work harder than my hearing colleagues to understand the hearing student and to speak in not only a second language, but in a second language mode. I was most comfortable and at most ease when teaching in ASL and teaching Deaf students.

From high school onwards to my current teaching position with the Department of Rhetoric and Writing, however, I have more experience teaching hearing rather than D/deaf students. Other than tutoring Deaf students, I interned as a high school English teacher at the Model Secondary School of the Deaf in Washington D.C., which required more thought on questions of pedagogy as English is most often a second language to D/deaf students, and one that we do not have full access to. I also had to reflect on the best ways to teach a dominant language via a minority language that is not often appreciated as a separate and complete language with grammatical rules different from the rules in English that they were expected to be proficient in. These pedagogical questions require a completely different mindset than do questions of teaching hearing students English via ASL because these students are not expected to be bilingual or to understand what I’m signing. The ASL interpreters are there to provide them with access to my instruction and to provide me access to their questions, comments, and insights. Hence, pedagogical questions of teaching hearing students are much more focused on the teacher-interpreter-student dynamic and facilitating communication in the most efficient way.

In order to do so, I include visual text as much as possible, and I share my lesson plans with the interpreters in as much detail and as early as I can. The interpreters that I work with have said, at times, that they love the “script” that I provide them. My lesson plans are probably more detailed than most, and I strive to provide my lessons as early as possible so the interpreters have more time to review and prepare for class. I think of teaching with interpreters as working with a team, and I need to take them into consideration as well as questions of translation and provide instruction to the interpreters as well as the students. These interpreter instructions most often relate to the signs that we should use—especially when certain English words are fingerspelled. I will create a sign whenever possible so that we do not need to repeatedly fingerspell lengthy English words.

Some people ask why I choose to sign rather than speak directly to my students. This question is one that I asked of myself when I began to teach at the college level. Before coming to the University of Texas at Austin, I had some experience teaching hearing students with interpreters, so I was already trained in advocacy and had instruction on best practices when working with interpreters under the “team” mindset. However, on a one-on-one basis with students or the primary teacher, I would often speak. I carried this practice over to my work as a Teaching Assistant at UT, and I would alternate between signing and speaking when students asked me to speak. But, I realized, over time, and as I developed more confidence, that I was just as effective as a teacher when I signed as when I spoke. I also realized I was doing a disservice to myself and to my community when I adhered to audist norms that privileged speech over sign. I was operating under the commonplace that students learn best from those like themselves. I was also teaching under audist pressures that prevented me from asserting my position as the one “in the front of the classroom”—or, as the teacher, the one who could determine the pace of the class. I was comparing myself to my hearing colleagues and feeling, like I did in high school, that I should “blend in” and be like them, or that I might be putting my students at a disadvantage if I was not like the other TAs.

However, I learned to put more trust in the team of interpreters that work with me, and I’ve worked on improving the teacher-interpreter-student dynamic by being more assertive and instructing my students on this dynamic from day one. I’ve found that by being straightforward and providing a simple clause about turn taking and participating in a class with interpreters, students are able to quickly adjust to the different communication dynamic. Several students are also fascinated by the different dynamic, which has worked to my advantage at times. In my years of experience thus far, I have not had troubles with classroom management or respect. I also feel that I connect more with minority students or with students for whom English is also not a first language. So, even though I’m not hearing like them, in another sense, I am like them, and I do a service to students and teachers—both hearing and Deaf—who are typically underrepresented in the educational establishment when I assert my identity and refuse to “pass” for someone other than who I am.

And, for full transparency, I should also disclose that I am fully aware of the ways that I am perceived as a role model, and that I knew I served as an ambassador to the D/deaf and hard-of-hearing community even before that role became official. Hence, as I considered the pedagogy of the Deaf teacher, I was thinking on a global scale and not only of myself. I believe in the abilities of all D/deaf and hoh teachers who are qualified to teach, yet, at the same time, when I first started teaching at the college level, I questioned my own best practices when it came to my specific group of students as their concerns and needs were utmost in my mind as well. With experience, and with the knowledge that other D/deaf teachers and academics work to teach hearing students, I came to the conclusion that I could both serve my students and my community in a way that benefitted us all—with the backing of the university, interpreters, and laws that protect the civil rights of deaf people—laws that recognize interpreters as professionals who provide a service that accommodates the communication needs of both hearing and deaf people. In the end, I will continue to refine my teaching methods along with my hearing colleagues, but I will also continue to refine my skills as a Deaf teacher so more articles like “Miss Deaf America Raises Awareness” and “Sound Teaching” are published and so less discrimination occurs—as detailed in an article published last year titled “Silence and Solitude,” for one tragic example.

---A side note: UT Newscast has produced a video of an interview with me as well as clips of my teaching, and an interview of one my students. I’m still waiting for it to be captioned, but I’ll post the link as a comment once it is captioned so you may have a brief, “inside” look at my teaching.

---Please feel free to post questions if I’ve left any unanswered, and I will answer them either as they appear, or in a future blog post on a more specific pedagogical topic.

[1] See Brenda Jo Brueggemann’s article, “The Coming Out of Deaf Culture and American Sign Language: An Exploration into Visual Rhetoric and Literacy.” Also see Brueggemann’s chapter, “On (Almost) Passing” in Lend Me Your Ear: Rhtetorical Constructions of Deafness for her discussion of “coming out” as a deaf person (82).

[2] There are two current general understandings surrounding the sign/signifier DEAF. The use of the capital “D” Deaf signifies Deaf culture and a person who identifies as culturally/ethnically Deaf. The use of the lower case “d” deaf signifies physical impairment, pathology, and the general audiological perspective on deafness as signifying lack—the loss of hearing.