Image Credit:

The Chalkboard Manifesto by Shawn R. McDonald

I am teaching 306 for the first time this semester. Apart from the typical anxieties and uncertainties of teaching a new format (and a lot of content that had thus far been foreign to me) things are going pretty well. More important, they seem to be going better every week. Of course there are still many things I struggle with. One of the most important ones to me is getting a decent group discussion going.

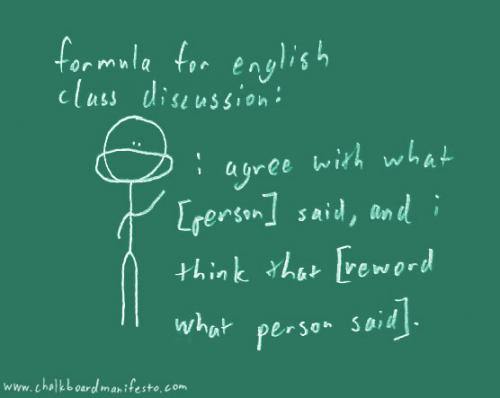

Now, my students grasp concepts relatively quickly, they ask sensible questions, make valuable contributions when explicitly asked to do so. They have things to say. So why are they so reticent when it comes to speaking their mind in discussions? One explanation may be that they are not used to articulating their own thoughts in the classroom, let alone defend them against other positions. Conversely, I feel like many of my students equate challenging their peers' comments with being rude, even backstabbing. And I feel a lot of this has to do with the way classroom discourse is channeled through me as a teacher. With so many assignments and deadlines and the emphasis so heavily on grades, I fear the primary way my students see me is as a distributor of letters from A to F. Hence the attempt to elicit direct teacher validation for any given comment and to see that validation as normative. If it is given, no need to explore or challenge further. All too often, this results in a sequence of instructor question → one or two answers → 20 heads nodding → silence.

So recently I've tried around with methods to take myself as a teacher out of the conversation more. In general it mostly works, although of course not always at a hundred percent. One resource I found very helpful to capitalize on was students' sense of competitiveness. For instance, last week I had the entire class get up out of their seats to watch the second presidential debate with them. At this point in the course, we are talking about ethos, pathos, and logos. So I told the students whoever could point out an appeal to either of these three and explain precisely how Romney or Obama made them could sit down. And we would not finish until everybody was seated. I expected this to take little more than 10 minutes, but it ended up taking up a good deal of the lecture. Because students talked. They contradicted each others' interpretations, elaborated what they understood about the three concepts much clearly and vividly than before and actually challenged some of my positions, which I loved.

I am not generally a big fan of foregrounding competition, and I would not do this exercise the same way. Although I stopped it before everyone was seated I felt a little bad afterwards for the students who were still standing towards the end. And I was not completely satisfied with the fact that I was still ultimately the one to make the call whether a case a student made was “good enough” for them to sit down. But I could imagine developing this further into a team activity with teams of three where two teams are challenging each other and the third has to decide who is making the better case. That way students will not only be doing rhetorical analysis, but actually have to construct rhetorically effective arguments on the spot. And they will not be able to turn to the instructor for validation.