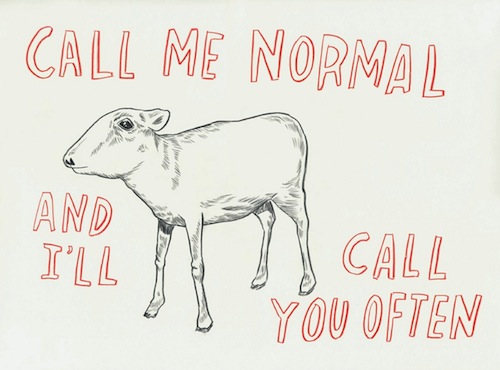

Image Credit:

Dave Eggers

At this point in the semester we’re all sizing up our latest batch of students. Not every student is the student who quietly does all her reading and eagerly contributes to class discussion. In fact, I’ve found that students like the one I just described can sometimes be the least stimulating. What’s fun or interesting about a student who hangs on our every word, and who repeats for us exactly what we want them to say? For those of us who teach reading and writing courses, one goal of our pedagogy will inevitably be imploring our students to think critically about their place in the world. If our students merely do what we say, to what extent can we ever consider ourselves successful? From a more selfish perspective, what fun would education be if we didn’t learn things from our students? I learned rather quickly my first semester of teaching that one of the easiest ways I can destroy my credibility as an instructor is to pretend that I know everything, that my students have nothing to teach me. The pretension is exactly what the student hanging on my every word wants.

But of course we all know students on the opposite extreme, the students who challenge us in various ways. These come in many guises. They can sometimes think they know everything, and try to correct us whenever they think we’re wrong or whenever we misspeak. They can be the student who is rather vocal about not liking several days’ reading in a row, and thus provide us instructors with the anxiety that class morale might be dipping on account of a few contagious sour patches. They can be the students who are only in our courses for the requirement or a top mark. They can be the students who contribute nothing except for a blank stare at their electronic media. These types of students are often the ones who have most to gain from a basic reading and writing course, and more often than not they’re the students we’re likely to remember years later.

For the student who thinks they know everything, it’s important that we listen what they have to say. For the student who’s vocal about not liking much of the reading, it’s important that we press them on what exactly they didn’t like, which moments in the text caused particular friction, and to encourage them to articulate their opinions in more exciting ways. For the student who’s only concerned about their grade, we can assign reading that discusses how many tech entrepreneurs dropped out of university. For the student who’s recedes into their computing device or phone, we can encourage them to find their own voice based on experience, and to take pride in that voice while listening to the other voices around them.

I’m not a psychiatrist, but it seems important that we don’t hold students accountable for issues that likely aren’t their fault. Just as soon as we treat our students like anybody else we’ll encounter in our short lives, it’ll immediately become apparent just how much they have to teach us.