Image Credit:

By Traitrnator

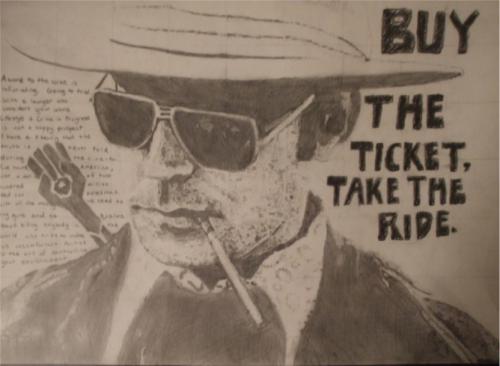

Awhile back I remember reading that, early in his career, Hunter S. Thompson began every morning typing word for word full chapters of The Great Gatsby. At one point in his early twenties, apparently, he’d typed out the whole book multiple times. As with most things Thompson, his friends and colleagues were baffled. When asked “why?” Thompson said “I want to know what it feels like to write something great.”

Now there’s two ways to respond to this: 1) Thompson—who was just as famous for his drug use as he was his pioneering “new” journalism style—was a lunatic and this habit represents just one more quirk to ad to a landfill of quirks or 2) Thompson, who, succeeded in spite (rather than because) of his drug use, had indeed stumbled onto something.

As you’ve probably guessed at this point, I chose the later; and, I decided to test out the thesis on my students. In my 309K course, after their first full paper assignment, many students were struggling with rhetorical analysis. As per usual, many just couldn’t quite get their heads around how analysis is supposed to look. What do you expect? What am I supposed to say? How is analysis different than opinion? What do you mean by “focus on the rhetoric”?

In the past, I’ve found that the best way to answer these questions is to meet with students one-on-one and illustrate, with concrete examples, how their papers are polemical rather than analytical or evaluative rather than substantive. After a bit of instruction most students tend to get the hang of rhetorical analysis and turn out decent work by the middle of the semester. But, with Thompson on my mind, I wondered if there might not be a better, and quicker, way to give students the feel for rhetorical analysis. So, I decided to ask my students to do something — something they, surely, have never been asked to do by a teacher before: copy another person’s work word for word.

I asked my students to take out Lunsford’s Everything’s An Argument (8th ed.), turn to page 108, and read David Brooks’s Times column “It’s Not about You.” After giving them a few minutes to complete the reading, I then asked them to read student Rachel Kolb’s analysis of Brooks’s essay entitled “Understanding Brooks’s Binaries.” Once they finish reading, I ask them to log-in to their nearest computer and open up a Word file and then type the piece word for word. Most students were shocked and I had to repeat myself multiple times.

“Yes, I really want you to copy her essay word-for-word, and, then print it out with your name on the top….give it the title "Imitation Exercise."”

As the class began typing, I surveyed the room and explained that I felt typing Kolb’s words—which are by no means perfect, but certainly competent—would help them not only see, but also feel, how analysis worked on the page.

I started the exercise with about 15 minutes left in the class and most of the students weren’t able to finish in time, so I allowed them to send it to me before the next class session. So far, most of the feedback has been overwhelmingly positive. Many of my students have commented that the exercise really helped them get a better feel for what was expected in rhetorical analysis. I have to say that their paper revisions were significantly improved across the board, and, in many cases far more than I expected. It’s worth also mentioning, that, thus far, no students have confused the intention of the exercise in any fundamental way. I haven’t received any papers copying whole phrases from Kolb’s work or, even cutting too close to her text, which, really, would be almost useless, since she is of course analyzing a completely different piece of rhetoric. I highly recommend giving an “imitation exercise” a try.

If you already require Everything’s An Argument, Kolb’s paper won’t require any printing; an exemplary work from a past student, or the edited student essays reprinted in the back of the textbook Critical Situations would work just as well. The key is making sure to have the original piece they analyzed to pair with the paper.

If you give it a try (and it works) don’t thank me, thank HST … and, if it fails spectacularly, please also direct the necessary blame his way as well :)