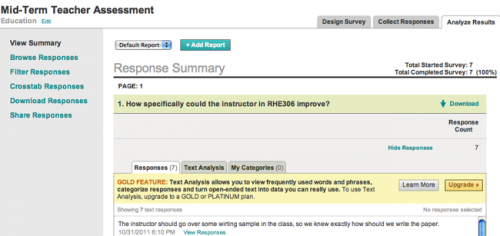

Image Credit:

Screenshot of Survey Monkey

Teaching is an art and teachers, like other artists, run the risk of valuing their performance too highly and overlooking their faults and mistakes. But as the true artist must ever abhor complacency, and tirelessly seek new angles on his or her work to spot frailities that can be avoided or improved in future, so the true teacher must resist the allure of self-sufficiency.

Teaching, even when successful, leaves no monument but in the student's mind. After the semester ends, many students we will never see again -- and if we do, rarely will we see them exercising the skills we taught. In short, our work is generally inaccessible to retrospective critique.

The worst vein of pollution I have witnessed in the graduate student experience -- and fortunately only infrequently -- arising perhaps from a combination of little sleep, long study and public irrevelance, is a kind of condescending or (in the worst cases) deprecating attitude some instructors take toward the undergraduates they teach. As if the dearth of post-modern continental theory among the undergrads were some kind of fault, rather than a token of good health and sound mind. The truth, as many of us continually re-learn, is that most of our students are delightful people, with a variety of interests and skills, and often with a fair degree of knowledge in their chosen fields, from whom, if we listen, we may learn.

Student evaluations of teacher performance have fallen under corrosive political debates about the nature of accountability and its role in the education system. Partisanship has made some teachers cynical about teacher evaluations in a society made cynical about teachers by partisanship. And even for those of us -- many of us -- who look forward to student feedback at the end of the semester, at least some anxiety about the outcome of the surveys lurks, born of the remembrance of one or two biting critiques from the past. If only we had known of that one student's gripes earlier, we could have done more to answer them, and perhaps made the class better for everyone.

Because I recently returned to teaching after three years in a different line of work, and this semester tried for the first time teaching Rhetoric and Writing, I doubted my performance perhaps more than usual. The idea of having students participate in a voluntary mid-term survey about my teaching performance struck me as a way to get a sense of students' assessments of my job at a point in the semester when time remained to correct myself if necessary. Anonymity would secure their sincerity. I went to SurveyMonkey and, with no prior experience of the site, quickly wrote up a survey with the following three questions:

1. How specifically could the instructor in RHE306 improve?

2. Is the instructor fair in leading class and grading assignments? Are assignments and the instructor's expectations clear?

3. Is RHE 306 an effective course? Are your writing skills improving? What would you change about the course, if you could re-design it?

Of eighteen students, only seven filled out the survey. The low response probably reflects the fact that the email they received said the survey was informal and optional. And I offered no incentives for taking the survey other than my gratitude, less than a pittance considering that it must be distributed anonymously. Perhaps in future I will make the survey mandatory. Nevertheless the seven responses I received were sufficient to teach me at least two important lessons, which I shall relate.

Most of the responses, whether from students' generosity or politeness, indicated general satisfaction. In response to the second question, several students said that the instructor "is fair," "does a good job," and that "assignments are very clear." To the third question, students said that the course is "effective," "a good challenging college course that makes a student think critically," and that the "workload is not excessive." One said it was becoming "easier to sit down and write papers faster and more clear" -- a positive assessment vitiated, given the purpose of the course, only by its grammar.

The teacher's duty is to smile and move on from these niceties. The purpose of surveys lies not in replenishing a self-esteem withered from excessive exposure to the Pierian Spring. Rather it is to discover our faults that we may amend them. My students' answers to the first question served this purpose. I framed the question in a way that would force a critical response: how specifically could the instructor improve? Each of the seven students concurred generally on the need for greater clarity on assignment expectations. The instructor could improve by "stating specific objectives and requirements of certain assignments," and giving "a clearer explanation of the assignments," and providing "more example essays." Though some of these comments flatly contradicted answers in the second question, the fact that they came first gave them priority -- students must have felt no need to repeat the same criticism in question two.

This survey therefore provided me with a student consensus that I needed to provide clearer explanations, examples and expectations for assignments. Because I already devoted what I considered excessive class time to explaining assignments, "teaching for the test," I felt some annoyance after reading these comments. But upon more mature consideration, a means of resolving the problem occurred to me. It was a low-fi, low-tech solution.

The next day in class I gave a pop quiz about the requirements for the upcoming assignment. Students had received warning from time to time since the beginning of the term that I might give pop quizzes, but to this point no occasion had arisen, as I had thought to spare them. Now I gave a quiz testing their comprehension of the essay soon due. After they took the first quiz, we graded it in class, giving students a chance to ask questions and learn answers from each other. Then I told them this surprise would not count toward their grade, but that the next one would count.

Few performed well on the pop quiz. Exposing their apparent lack of attention to the details of the approaching assignment must have stung them into paying more attention, since the essay results bore a much closer resemblance to the prompt, and similarity in form to each other, than previously. Before the next essay came due, I quizzed them again. Most students performed very well on the quiz -- they had studied the assignment -- and the essay's results corroborated this evidence. Most of the students even seemed to enjoy the quiz this second time -- they seemed to relish what they viewed as earning easy points.

Thus I learned of a danger of my own teaching style -- lack of clarity, and sometimes downright confusion, about the nature of assignments -- and students learned of their responsibility to understand assignments and to ask for clarification if they do not.

I shall quote only one other student's comment in the anonymous survey: "Make the course a little more interesting. I know that's every student's dream, but that's all we can ask for a class that early." This I have attempted to do by introducing more multimedia into lesson plans than previously, though I still resist any drift toward college class as variety show.