Image Credit:

Tweet by @AriFleischer, fmr. Bush Press Secy.

Marking 9/11

This year, in 2012, my first-year rhetoric students were mostly third graders, seven- and eight-year-olds, on 9/11/2001. Their memories of 9/11 were cloudy, mostly of a fearfulness they didn't fully understand. Some of them remember leaving school with their parents; others remember staying in classes with TVs on, watching the news report on what was happening. That's what I did as a high school student on 9/11.

Because I'm teaching Crowley and Stancliff's rhetoric textbook Critical Situations, 9/11 is a thread that runs through our class conversations all semester. The example of 9/11 is used to illustrate many of the rhetorical themes and concepts in the book. On 9/12 this year, I took an opportunity to turn my class's attention more fully to the powerful issues attending 9/11 and the conflict between the official account of what happened on 9/11 and the revisionist accounts, more commonly known as conspiracy theories. Students had read the Critical Situations chapter on ethos, and I planned the following exercise and discussion.

Summarizing: Neglected Intel

We began by reading and summarizing a NYT op-ed by Kurt Eichenwald. In "The Deafness Before the Storm," Eichenwald argues that the Bush Administration neglected intelligence information in advance of 9/11. He suggests, though he does not explicitly claim, that this intelligence could have been used to avert the attacks. In fact, in his conclusion, he claims that we cannot ever know whether the attacks could have been averted. His relies on his reading of spring and summer 2001 presidential intelligence briefings, preceding the famous August 6 briefing, that warned of Al Qaeda's intentions and plans to attack the United States on US soil. There were even arrests made in connection with 9/11 that subsequently lead nowhere. Meanwhile, neoconservatives in the Bush Administration were advocating war against Iraq, going so far as to argue that "Bin Laden was merely pretending to be planning an attack to distract the administration from Saddam Hussein" (2). Students identified the main and supporting claims quickly--even though the article was a bit technical, it was brief.

Ethos: "9/11 Truther"

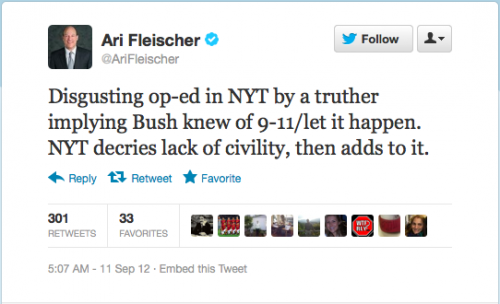

Then we shifted our discussion from summary to ethos by watching a clip from Rachel Maddow's interview with Kurt Eichenwald (question begins at 7:45). Maddow's last question for Eichenwald is about a tweet from former Bush Administration Press Secretary Ari Fleischer, in which Fleischer called Eichenwald a "truther" because of the op-ed. Maddow glosses the epithet "truther" as a charge that one thinks "9/11 was an inside job," adding "that therefore you should be dismissed as a crazy conspiracy theorist." Eichenwald accedes to the characterization of "truthers," adding to it the notion that "George Bush intentionally orchestrated 9/11," and then argues that his article is a purely factual description of the "real history" of 9/11. Eichenwald rejects the label "truther" and rebukes Fleischer's use of the epithet. After we watched the clip, I asked my students to discuss the issues of ethos at play in the exchange.

Students Respond

The first thing my students remarked on was not the way Fleischer aims to damage Eichenwald's credibility by calling him a "truther," nor the way both Maddow and Eichenwald concede that actually being a truther would have Fleischer's desired effect. It was not the way the epithet collapses a range of revisionist accounts or "counternarratives" into egregious and crazy conspiracy theory. We did discuss all those things, but the first thing my students remarked on was the damage Fleischer does to his own credibility by reacting to Eichenwald with dismissive anger, refusing to engage his article's claims. I think doing the summary exercise before the ethos discussion gave students to see Eichenwald's argument on its own terms, and not on Fleischer's. So, did they think Eichenwald was a truther?

The answers were mixed. Students agreed to the summary of Eichenwald's argument as carefully moderated; not overstated based on the evidence he cites. The Bush Administration neglected critical information in advance of 9/11. But, most students thought calling Eichenwald a "conspiracy theorist" implied a belief that 9/11 could have been stopped and that the Bush Administration neglected intel on purpose. One student was sure this belief could be fairly attributed to Eichenwald, even claiming Eichenwald's position likely meant he was not a Republican; still, the same student agreed that Eichenwald's article did not make those claims explicit.

The pedagogical goal of our discussion included but also exceeded helping students get a handle on summary and ethos. I think Critical Situations gives us examples from 9/11 (and from the early American feminist movement) as deliberately charged rhetorical examples. They are available to be worked over with our students because the controversies they inspire are still unfolding. The currency of the materials we used helped students remember the huge footprint 9/11 left on our nation's policy and on our political imaginary. My hope is that our discussion of the widely despised debate over "9/11 Truth" showed students how this debate puts one's credibility at stake as it constrains what is sayable, or hearable, about 9/11 today.